Bacterial vaginosis

Definition - What is Bacterial Vaginosis?

Bacterial vaginosis is an overgrowth of the vagina with so-called pathogenic germs. These germs occur partly in the vaginal flora and are partly transmitted through sexual intercourse. If there is an imbalance in the natural vaginal flora to the detriment of the important lactic acid bacteria in the vagina, other germs can increasingly settle. This imbalance changes the pH of the vagina. This is an important criterion for bacterial vaginosis.

Concomitant symptoms

Many women do not even notice bacterial vaginosis because it does not necessarily cause symptoms. However, when symptoms are present, a change in vaginal discharge is almost always observed. The discharge is typically thin or foamy and gray-white to yellow.

Furthermore, an unpleasant, fishy odor is very characteristic of bacterial vaginosis. The smell is caused by the breakdown of proteins by the bacteria. Other symptoms, while rare, can also be present. These include burning vaginal pain during sexual intercourse, known as dyspareunia.

Burning sensation when urinating and vaginal itching are also possible. General symptoms such as fever and pelvic pain are more likely to suggest an ascended infection, such as uterine or ovarian inflammation. However, they are atypical for bacterial vaginosis.

Find out more about the topic here: Vaginal discharge

Causes - How does bacterial vaginosis develop?

The causes of bacterial vaginosis are not fully understood, but there are some mechanisms that promote its development. First of all, it is therefore important to understand how the healthy vaginal flora works.

The so-called Döderlein bacteria are found in the natural vaginal flora. These are lactic acid bacteria that are responsible for the acidic pH of the vagina. The acidic pH protects the vagina from ascending infections. Various factors, such as frequent sexual intercourse, incorrect or excessive intimate hygiene, antibiotic therapies and the introduction of foreign bodies (e.g. sex toys) can change the vaginal flora.

Although frequent sex and frequently changing sexual partners are among the risk factors for bacterial vaginosis, it is not a sexually transmitted disease in the traditional sense. Rather, changes in the vaginal environment lead to germs that are already in the vagina or temporarily resident germs multiplying many times over. The balance is then not on the side of the natural Döderlein flora, but on the side of the pathogenic germs.

Which bacteria are causing this?

In bacterial vaginosis, an imbalance in the bacterial colonization of the vagina leads to unpleasant symptoms such as itching and burning. Various pathogens are involved in this clinical picture. These are pathogens that are already in the vagina, or pathogens that only temporarily colonize the vagina.

The most common germ that causes bacterial vaginosis is the bacterium Gardnerella vaginalis. This rod bacterium is part of the natural vaginal flora. If the balance is disturbed, Gardnerella vaginalis multiplies a hundredfold and causes discomfort. Apart from this bacterium, there are also some other pathogens in bacterial vaginosis, such as Mobiluncus or Prevotella. The number of Döderlein bacteria, which are very important for a healthy vaginal flora, decreases.

What are the risk factors?

The exact causes of the occurrence - especially the recurrence of bacterial vaginosis - are not yet fully understood. However, there are a number of risk factors that can make bacterial vaginosis more likely.

Frequently changing sexual partners and more frequent, especially unprotected, sexual intercourse, for example, are important risk factors. However, sexual contact does not lead to the transmission of a germ that causes the disease, but seems to lead to an imbalance in the vaginal flora in a different way.

Other risk factors include frequent vaginal douching and the use of cosmetic products in the genital area. Stress and low social status also seem to be associated with an increased incidence of bacterial vaginosis.

In addition, bacterial vaginosis occurs more frequently after systemic antibiotic therapy. Antibiotic therapy can change the flora of the vagina as an undesirable side effect. This makes it easier for germs such as Garnderella vaginalis to multiply in an uncontrolled manner. An estrogen deficiency, such as occurs during the menopause or during the puerperium, is a risk factor for bacterial vaginosis.

Also read: Mixed infections - bacterial vaginosis and vaginal thrush

How is the transmission route?

Bacterial vaginosis is not actually a communicable infection. Unlike HIV or syphilis, for example, it is not transmitted directly through sexual intercourse. Various factors, including frequent sexual intercourse or frequently changing sexual partners, lead to an imbalance in the vaginal flora.

Bacterial vaginosis is mainly caused by bacteria such as Gardnerella vaginalis, which are already found in the natural vaginal flora. These pathogens are not transmitted from outside to the woman. Therefore, in the case of bacterial vaginosis, unlike, for example, a chlamydial infection, the partner does not have to take part in treatment.

How contagious is that?

Bacterial vaginosis occupies a special position among gynecological infectious diseases. Unlike an infection with chlamydia or HP viruses and trichomonads, bacterial vaginosis is not directly contagious. It is true that the woman's sexual partner often also carries the causative germ, namely Gardnerella vaginalis.

However, this germ is usually without disease value. It is also referred to as facultative pathogenic. This means that the pathogen can cause disease, but does not have to. Bacterial vaginosis is therefore basically not contagious. Nevertheless, protected sexual intercourse should be practiced as part of treatment and also with regard to the prophylaxis of other diseases, especially with changing sexual partners.

diagnosis

The so-called Amsel criteria exist for the diagnosis of bacterial vaginosis. At least three of the four blackbird criteria must be met in order to be allowed to diagnose “bacterial vaginosis”. The blackbird criteria are determined on the basis of various studies.

One criterion is the presence of an increased amount of liquid or foamy, gray-white to bleached fluorine. The gynecologist sees this fluorine during a vaginal examination. You may also notice reddening of the vagina.

The second blackbird criterion is the fishy smell of the vagina. This can be reinforced by the amine test. In this test, the doctor drips a solution of potassium hydroxide onto some smear material from the vagina. The lye increases the fishy smell.

With the help of a pH strip, the gynecologist will continue to determine the pH value on the inner wall of the vagina. If this is above 4.5, another blackbird criterion is met.

To examine the last blackbird criterion, a smear from the inner wall of the vagina is examined under the microscope.

There are so-called key or clue cells. These cells are exfoliated cells from the vaginal surface that are colonized with bacteria. In unclear cases, a bacterial culture can also be set up. For this, a smear is taken from the vagina and the bacteria are allowed to grow on special nutrient media. As a routine examination, however, this examination has no value in bacterial vaginosis.

treatment

Bacterial vaginosis therapy involves the use of various antibiotics that fight the bacteria. Therapy must always be carried out to prevent complications such as ascending infections. A distinction is made between systemic and local therapy. The active ingredients clindamycin or metronidazole are suitable for systemic therapy. The active ingredient clindamycin is taken at a dose of 300 mg three times a day for a period of seven days. Metronidazole is taken once a day, preferably in the evening, in a dose of one gram, also for seven days.

As an alternative to systemic antibiotic therapy, vaginal creams or suppositories can be used. The active ingredients clindamycin or metronidazole are also used for local therapy. Aside from antibiotic therapy, there are other supportive measures available for the treatment of bacterial vaginosis. Since the vaginal pH value plays a very important role in the healthy vaginal flora, it is advisable to acidify the vagina. Vaginal suppositories that contain lactic acid bacteria are suitable for this. They are inserted deeply into the vagina for about seven days before bed.

The use of unsweetened natural yogurt is sometimes discussed as a therapeutic approach. The natural yoghurt also contains lactic acid bacteria and can be applied deep into the vagina by hand or a syringe. Both vaginal sprays and vaginal tablets with disinfecting agents are available for disinfecting the vagina.

You might also be interested in this topic: Therapy for bacterial vaginosis with Vagisan®

Does my partner have to be treated as well?

The co-treatment of the partner is not necessary in the case of bacterial vaginosis. Gardnerella cells, which can be detected in urine, semen or urethral swab, are usually found in the partner, but this has no disease value. Co-treatment leads to the elimination of the bacteria, but cannot prevent a relapse of the disease (relapse) in women. In studies, therefore, no results could be obtained that would speak in favor of co-treatment by the partner. The use of antibiotics should always be considered with regard to their benefit, as the uncontrolled intake of antibiotics can develop resistance to germs.

Duration

Bacterial vaginosis can usually be treated very well within a few days through the use of antibiotics. The symptoms also improve quickly below this, so that healing occurs after 7 days at the latest. Unfortunately, relapses are common, which is why women who have had bacterial vaginosis tend to develop other bacterial vaginoses. If left untreated, bacterial vaginosis can become chronic and cause discomfort for weeks or months. Often the symptoms are not always present, so that after the symptoms have subsided in the meantime, the symptoms can spontaneously flare up again.

Possible complications

Bacterial vaginoses are usually treatable and heal without consequences. However, they can also come with certain complications.

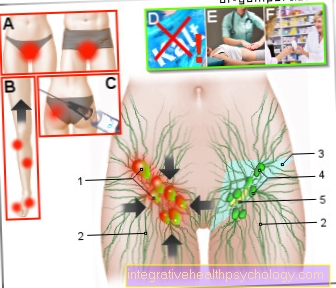

If left untreated, there is a risk of so-called ascending infections of the female genital organs. These are infections of the internal genital organs, such as ovarian and uterine infections, which are caused by germs rising from the vagina. In the worst case, such infections can even lead to sterility. Therefore, bacterial vaginoses are always treated with antibiotics. Especially after operations and interventions, such as scraping or the insertion of a coil, the risk of an ascending infection from bacterial vaginosis is increased. Therefore, bacterial vaginosis should always be excluded prior to such treatments.

The imbalance in the vaginal flora also increases the likelihood of sexually transmitted diseases such as HIV. The non-intact vagina is less able to fight off infection in this condition, which is why unprotected sexual intercourse in such a situation is associated with an even higher risk of infection than usual. Bacterial vaginoses can also lead to special complications during pregnancy (see pregnancy section).

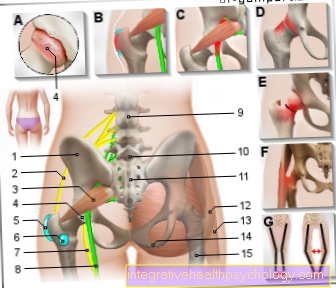

Bacterial vaginosis in pregnancy

Bacterial vaginosis can also occur during pregnancy. In this case, treatment is particularly important as there is a clear link between bacterial vaginosis and the onset of premature birth. The risk of a miscarriage is also increased. Especially in the last trimester of pregnancy, the risk of premature birth due to bacterial vaginosis is increased. It probably leads to premature labor and premature rupture of the bladder through various mechanisms.

One possible cause is the increased formation of so-called prostaglandins, which arise as part of inflammatory reactions. As a further complication, bacterial vaginosis can lead to an amniotic infection syndrome. This is an infection of the amniotic fluid that can lead to a life-threatening infection of the newborn. In addition, amniotic infection syndrome can cause blood poisoning in the mother and is therefore a very serious complication of bacterial vaginosis in pregnancy.

However, bacterial vaginosis can have serious consequences not only during, but also after pregnancy. Especially after a caesarean or perineal incision, it can lead to infections and wound healing disorders of the uterus.

So bacterial vaginosis is treated even if it doesn't cause symptoms. As soon as a germ is detected in the course of the preventive medical check-ups, it is treated with antibiotics. The therapy takes place in the first trimester of pregnancy with a vaginal cream with clindamycin. In the second and third trimester of pregnancy, like outside of pregnancy, the therapy is treated with metronidazole and clindamycin in tablet form. If there is a threat of premature birth, high-dose antibiotics, namely metronidazole and erythromicin, are used for treatment.

.jpg)