prostate

Synonyms

Prostate gland, prostate cancer, prostate enlargement

English: Prostate, Prostate gland

definition

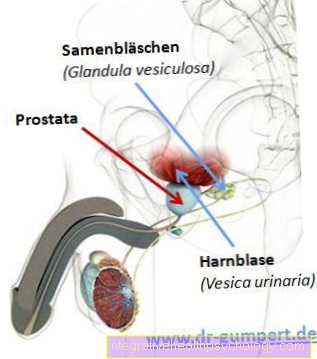

The chestnut-sized prostate gland (prostate) is a gland reserved for the male sex (so it only exists in men), which releases the substances (secretion) it produces into the urethra.

Whenever a gland discharges its secretion onto an internal surface of the body (with the exception of the blood vessels), as is the case for the interior (lumen) of the urethra, one speaks of an "exocrine gland".

As such, the prostate, along with the vesica seminalis and the Cowper's glands (glandulae bulbourethrales), is one of the so-called "accessory" glands Sex glands“Of the man, which together ensure the chemical change (modification) and maturation of the sperm during and after the ejaculation.

In the female sex there is a largely corresponding gland, the "paraurethral gland" (glandula paraurethralis, Skene gland, prostate feminina), which can lead to female ejaculation when sexually stimulated in the area of the G-spot.

The secretion reaches the urethra, vagina (vagina) and vaginal vestibule (vestibulum vaginae).

In the following, we would like to limit ourselves to the male gland, which weighs around 20 grams, as this is much more common due to diseases.

Function of the prostate

The prostate is a gland that produces a secretion, which in the ejaculation (ejaculation) is released into the urethra and thus to the outside. The prostate secretion makes up about 30% of the seminal fluid. The PH value of the secretion is about 6.4 and is therefore somewhat more basic than the acidic level in the vagina (Scabbard). As a result, the prostate secretion increases the likelihood of survival Sperm in the acidic vaginal environment.

The prostate secretion also contains other substances which, on the one hand, affect the mobility of the Sperm act as well as make the ejaculate overall thinner. The latter substance, which acts on the thin fluid of the ejaculate, is the so-called prostate-specific antigen (PSA), which can also be detected in the blood for diagnostic purposes.

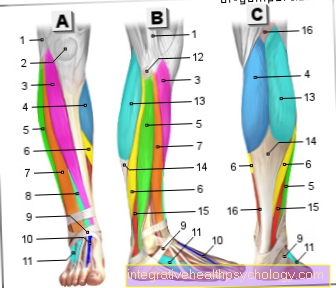

Illustration of the prostate

Prostate = prostate gland

- Prostate - prostate

- Peritoneum cavity -

Cavitas peritonealis - Ureter - Ureter

- Urinary bladder - Vesica urinaria

- Male urethra -

Urethra masculina - Male limb - penis

- Testicles - Testis

- Rectum - Rectum

- Vesicle gland

(Seminal vesicle) -

Vesicular gland - Urine (urine) - Urina

- Bladder neck

(internal sphincter) - Glandular tissue of the prostate

- pelvic floor

(external sphincter) - Anterior zone

- Inner zone

(Transitional zone) - Central zone

- Outside zone -

peripheral zone - Spray channel -

Ejaculatory duct

You can find an overview of all Dr-Gumpert images at: medical illustrations

Macroscopic anatomy

Where do you look for that organ that resembles an apple cut in half and worries so many men?

An introduction to the structure of the pelvis is required to explain their anatomical position on the man in a comprehensible way.

The pelvis (pelvis) resembles a funnel that slopes forward. Upwards (cranial) it goes over without separation into the abdominal cavity, the lower (caudal) narrow opening of the pelvis (the funnel) is closed by muscles and connective tissue, the unit of which is called the “pelvic floor”.

In this area, a specialist expects the prostate. The prostate is embedded exactly between it and the urinary bladder (vesica urinaria), with its chestnut-like shape wrapping around the male urethra in a ring.

This can be imagined as if a clenched fist (prostate) grasps a straw (urethra).

Directly above the prostate, the urinary bladder finds its place under the bowels of the pelvis. Because of this, the prostate supports the bladder neck and thus the natural closure of the urinary bladder.

Next to (lateral) as well as below (caudal) the prostate lies the pelvic floor, which it partially penetrates with its tip, while its base, as mentioned, lies above the urinary bladder.

Furthermore, the prostate gland is accessible via the perineum, both for surgery and for massage.

In addition, it is of the utmost importance to know what is in front of and behind the prostate.

In front of her lies the "puboprostatic ligament", a small ribbon that she hangs on the pubic bone (os pubis, part of the hipbone).

Behind it, however, is the far more important positional relationship to the end of the gastrointestinal tract, the rectum. Only a thin membrane of connective tissue (fascia rectoprostatica) stands between them. This makes it possible to touch (palpate) the prostate from the rectum (from the rectum), to visualize it using ultrasound (transrectal ultrasound, TRUS) and to operate.

Changes in their usually coarse, resilient composition on a smooth and even surface are usually not lost on the fingers of the experienced doctor.

This process is called a "digital rectal exam" (DRE).

With the knowledge of the location of this gland, we approach its function.

How does the secretion of the prostate get to its place of action and why do we need it anyway?

In order to answer this question, the production and derivation system of the male semen must first be clarified. The freshly obtained ejaculate is called "sperm" and consists of cells, the "sperm" (synonym spermatozoa, singular spermium / spermatozoon), and the seminal fluid. While the cellular components come from the testes (testis), the fluid is mainly obtained from the accessory sex glands, which also include the prostate.

The spermatozoa (sperm) are known from everyday depictions: mostly drawn in milky white with a small head and a long, flexible tail (flagellum), the sperm threads whiz through a wide variety of scenarios.

By the way, they carry the male genome in their heads in the form of 13 chromosomes (half (haploid) chromosome set) in order to fuse with a female egg cell (ovum) to form new life in the ideal theoretical case.

Under extremely complicated regulation, the spermatozoa arise in the testes and pass through the ducts of the epididymis (epididymis) into the vas deferens (ductus deferens). This forms with numerous other structures to form the spermatic cord (Funiculus spermaticus), which finally runs through the well-known inguinal canal (Canalis inguinalis) on our abdominal wall.

Later, the vas deferens meet within the prostate with the central excretory duct of the bladder gland (ductus excretorius). After the union, the new vessel is simply called the “ejaculatory duct” (ductus ejaculatorius), which opens into the part of the urethra that is embraced by the prostate (pars prostatica urethrae). There the spray canal ends on a small elevation, the seed mound (Colliculus seminalis).

The numerous excretory ducts of the prostate gland draining the prostate gland into the urethra flow directly to the side of the seed mound. The urethra now penetrates the second layer of the pelvic floor (urogenital diaphragm), no longer wrapped by the prostate, and runs within the penis up to its opening on the glans (glans penis).

If you look at the prostate from the outside, it is often divided into lobules. The right and left lobes (lobus dexter et sinister) are connected to one another by a middle lobe (isthmus prostatae, lobus medius).

Every complete description of an organ in medicine also includes a reference to the organization of the blood and lymph vessels as well as the nerve tracts. Blood supply and lymph drainage of the prostate arise from the connection to vessels of the urinary bladder and the rectum.

The nerves that reach the prostate mainly come from the so-called “vegetative nervous system” (autonomous nervous system). They control their activity and the shortening (contraction) of the local muscles (see below), but are not able to convey pain into the consciousness of the man.

Prostate and urinary bladder

Here an incision was made parallel to the forehead (frontal incision): the prostate encompasses the urethra. Inside the urethra, a little mound bulges into its interior, the seed mound. A small injection canal with the preliminary sperm ends on this from each half of the body. The numerous excretory ducts of the prostate flow into the urethra right next to the seed mound!

- bladder

- urethra

- prostate

- Seed mound with the two openings of the spray tubules

- Excretory ducts of the prostate

Microscopic anatomy

In addition to the previous description (macroscopic anatomy) there is also one that is made with the aid of tissue theory (microscopic anatomy, histology).

For this purpose, a prostate (the "preparation" in the histological vocabulary) is cut into wafer-thin slices, the fluid is removed from it, it is allowed to react with certain dyes and it is properly fixed on a pane of glass (carrier).

The preparation now offers the opportunity to be examined under a microscope. In the ordinary light microscope, the impresses Prostate gland with the actual gland cells (Epithelial cells), which pour into the associated execution corridors.

As a seemingly disordered system of tubes, the passages end, as we already know, in the urethra.

The fibrous connective tissue spaces between the glands and ducts fill a noticeable number of "smooth" (not arbitrarily usable) muscle cells that serve to expel the secretion and to open and clamp ducts (see below).

If the entire prostate gland is found in cross-section, three zones of the prostate can be distinguished, which lie concentrically around one another like the Russian babushkas / matryoshkas based on the "doll in doll" principle:

- The first, so-called “periurethral” zone, as the smallest and innermost zone, encompasses the urethra and is closely related to it in terms of developmental history (embriological).

- The “inner zone” is the name given to the second layer, which makes up around a quarter of the tissue mass. Its connective tissue spaces are particularly tightly packed, and the injection tubules (ductus ejaculatorius) run in it.

- The remaining space, almost three quarters of the prostate, is taken up by the “outer zone”, which is only connected to the outside by the tough capsule. This is where the lion's share of secretions takes place. The actual cradle of this production lies in around 30-50 glands, which are lined with thousands of hard-working cells. In all glands and many other hollow organs, the innermost cell lining of the cavities is called "epithelial cells". They represent the walls of the cavities (clearing, lumen) and pour their specific substances into them. This is exactly where the actual work of the glands takes place, the specialist speaks of the "parenchyma" of the organ or gland. "Prostate stones" can often be seen within the glands, but these are only thickened secretions and are not of a pathological nature at first. It is particularly important to know that the different zones respond to different hormones, which we will deal with later in the case of the pathological processes. Instead of the terms inner / outer zone, the pair central / peripheral zone is also used.

Microscopic representation of the prostate

This figure shows a wafer-thin section through the prostate, magnified 10 times.

The individual glands are bounded by many small epithelial cells, which are marked green in the central gland (2). Light pink colored prostate secretion often completely fills the interior of the glands. Beyond the glands is the fibrous connective tissue, in which smooth muscle cells are embedded like a school of fish.

- connective tissue

- Prostate gland with epithelial cells marked green in places

Diseases of the prostate

If you have followed the previous topic carefully, there will be no more surprises for the description of the typical pathological processes (pathologies) around the prostate!

First of all: every man has a prostate, relatively many of them would have to be classified as "pathological" from a medical point of view, but only a fraction of these actually cause symptoms! This fact forces the patient to make a very special trade-off between treatment and non-treatment.

One of the most significant diseases in men in terms of numbers is that of all

- malignant prostate cancer (prostate cancer),

- This contrasts with a benign disease called "benign prostatic hyperplasia" (BPH).

Often the two terms are popularly confused, as both have something to do with prostate tissue growth.

In addition to these medical elephants, prostate cancer and benign prostatic hyperplasia, there are other diseases. It is worth mentioning the mostly bacterial inflammation of the prostate gland (prostatitis) as well as the generic term “prostatopathy”.

Read more on the topic: Inflammation of the prostate

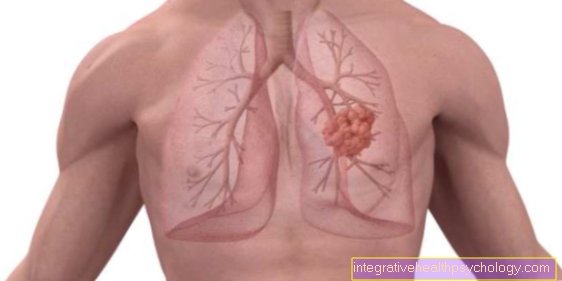

Prostate cancer

The Prostate cancer (Prostate cancer) is a malicious (malignant) Neoplasm (Neoplasia) in the prostate (Prostate gland) and is the most common cancer in men (25% of all cancers in men).

It is an illness of the older man and usually occurs first after the age of 60 on.

Prostate cancer can be classified according to its appearance and the location of the cancer. Prostate cancer is one in approx. 60% of cases Adenocarcinoma and in 30% one anaplastic carcinoma. In rarer cases, prostate cancer develops from other cells (Urothelial carcinoma, squamous cell carcinoma, prostate carcinoma). Macroscopically, the prostate cancer appears as a coarse and gray-whitish focus in the glandular tissue of the prostate.

In most cases (75%) these foci are located in the lateral parts of the prostate (so-called peripheral zone) or in the rear part (central zone). In about 5-10% the cancer lies in the so-called transition zone of the prostate and in 10-20% the place of origin cannot be clearly identified and named.

Symptoms of prostate cancer

Prostate cancer often shows no symptoms in the early stages, i.e. at the beginning of the disease (asymptomatic). If the disease is more advanced, there may be different ones Discomfort when urinating (micturition) or a erection come.

This includes symptoms such as frequent urination (Pollakiuria) in which only very small amounts of urine are released. This can also be painful (Dysuria). Often the urinary bladder can no longer be properly emptied, the urine stream is weakened and there is only more so-called urine dripping (the urine only comes off in drops) or interruptions in the urine stream. If the urinary bladder is not emptied properly, this leads to residual urine in the urinary bladder.

If the prostate cancer is already advanced, blood can also be found in the urine. Lower back pain can also occur. These are caused by metastases from prostate cancer that often spread to the bones.

Classification

Prostate cancer can be in different stages (I, II, III, IV) to be grouped. This is done by estimating the size and extent as well as with reference to possible lymph node involvement and metastases.

Diagnostics

Prostate cancer is diagnosed using a detailed medical history and urological examination as well as further diagnostics such as ultrasound and laboratory tests. The diagnosis can be confirmed histologically via a biopsy, i.e. a sample taken from the prostate. Furthermore, examinations such as roentgen, Magnetic resonance imaging and Skeletal scintigraphy carried out to assess the extent and progress in other tissues as well.

therapy

There are various treatment options for prostate cancer. Depending on the age of the patient and the degree and size of the tumor, a choice can be made as to whether treatment is to be carried out directly or whether it is only to be waited for. With this so-called watchful waiting or even that active surveillance the tumor is monitored and controlled more closely so that another form of therapy can be used at any time.

If the general condition of the patient is good and the life expectancy is more than 10 years, a radical prostatectomy can be performed. Here, the entire prostate is removed as far as parts of the vas deferens and the vesicle gland. Lymph nodes are also removed here. Radiation treatment is recommended after the operation.

If the general condition of the patient is not good enough for an operation, radiation therapy can be carried out directly and solely.

If the prostate cancer is too advanced (stages III and IV) then hormone withdrawal therapy can be carried out. This rarely brings a survival advantage, but reduces further complications caused by the tumor. If hormone withdrawal therapy fails, chemotherapy can also be used. However, this is also only used palliatively.

Inflammation of the prostate

The Inflammation of the prostate (Prostatitis) is a relatively common disease of the prostate. It is usually triggered by gram-negative bacteria, and inflammation caused by the bacterium is particularly common Escherichia coli. However, sexually transmitted diseases, such as through Chlamydia, Neisseria gonorrhoeae or Trichomonads, one Prostatitis trigger.

A distinction is made between the acute form and the chronic form, which can result from an unhealed and persistent acute prostatitis. In most cases, acute inflammation of the prostate is caused by the germs rising up (ascending infection) through the urethra into the prostate ducts. The inflammation is very rarely hematogenous, i.e. it is carried over to the prostate via the blood or when the infection spreads from a neighboring organ.

Symptoms of inflammation are pain, which is mostly rather dull and causes pressure in the perineal area. The pain can radiate into the testicles and also occur more frequently during bowel movements. It can also lead to urination disorders, i.e. problems with urinating. This would be difficult and painful urination (Dysuria), frequent urination in only small amounts (Pollakiuria) or increased urination at night (Nocturia).

In the case of acute inflammation, it can also elevated temperatures and chills come. Very rare symptoms are pyospermia (Pus in the ejaculate) or hemospermia (Blood in the ejaculate) as well as prostatorrhea (cloudy prostate secretion emerges from the urethra during urination).

The prostatitis will have a medical history and clinical examination as well Ultrasound of the prostate and one Urine sample diagnosed. Uroflowmetry or ejaculate analysis are also available as diagnostic options.

In acute cases, prostatitis is treated with antibiotics. Co-trimoxazole or gyrase inhibitors are mainly used here. These are given for about 2 weeks, in the event of complications over a maximum of 4 weeks. If urinary retention occurs during the inflammation, the use of a suprapubic catheter, i.e. the urinary drainage through the abdominal wall, is necessary. If the prostatitis is chronic, it is often more difficult to treat. Antibiotics but also pain relievers, spasmoanalgesics and alpha-receptor blockers are also used here.

If there is an abscess in the prostate during prostatitis, it can be punctured under ultrasound guidance. If the chronic prostatitis does not respond to therapy, removal of the prostate may be indicated.

In the acute form, it is important that antibiotics are used for a sufficiently long time to prevent the development of chronic prostatitis.

Enlargement of the prostate

The Enlargement of the prostate begins from the age of 35 slow and from the age of 70 is one for many men benign enlargement (benign hyperplasia) of the prostate. The prostate is known to be divided into several areas and the enlargement usually begins where the urethra runs through the prostate (periurethral area).

It follows that the prostate enlargement presses on the urethra, it constricts and it closes Discomfort when urinating can come. For example, the urine stream is weakened, the urine cannot be completely excreted and residual urine remains in the bladder, which is why you have to go to the toilet more often and even at night. The consequences of this affect the kidneys and can damage them in the long term.

To date, the cause of prostate enlargement has not been clarified and several theories are being discussed, ranging from hormone metabolism processes to interactions between prostate tissue.

Prostatic hyperplasia can be divided into 3 stages subdivide, which can be broken down according to the complaints. Stage I is characterized by difficulty in emptying the bladder, which can sometimes be painful. In addition, it is more common for those affected to have to go to the toilet at night. The first changes can also be seen in the urine stream when urinating: the beginning of urination is more difficult and the urine stream is no longer as strong as it used to be. This weakening of the stream can be recognized, for example, by whether you can still urinate over a garden fence. In stage I, however, no residual urine remains in the bladder, and it is still possible to completely empty the bladder by urinating.

The further stages are characterized by progressive symptoms. At first, a residual urine of more than 50 milliliters remains in the urinary bladder (stage II), then damage to the kidney from the enlarged prostate becomes manifest (stage III). The division into these stages takes place after discussions and extensive examinations by the doctor. In addition to the conversation and physical examination, an ultrasound examination and laboratory tests are also important.

The Therapy of prostate enlargement takes place at small magnifications initially with medication, in later stages or in the case of major complaints, a surgical removal of the prostate in question. If left untreated, an enlarged prostate can also trigger further problems. These include urinary tract infections that are triggered by the residual urine, but also painful urinary stones that can still trigger urinary congestion.

In summary, one can say that prostate enlargement is not a malignant disease or is to be regarded as a preliminary stage of a malignant disease, but can trigger some unpleasant symptoms, which is why therapy and the alleviation of the symptoms should be sought.

Prostate check

The prostate can be opened by means of a digital rectal palpation examination be well examined and assessed. This examination is best done in the side position. It is important that the patient is as relaxed as possible.

The examiner can first assess the anus from the outside. Then he inserts a gloved finger into the patient's anus (digital-rectal). Lubricant is used for this. The proximity of the prostate to the rectum makes it easy to feel the prostate through the wall of the intestine. The examiner assesses the condition (Consistent), the surface and shape of the prostate. This examination also pays attention to the function of the sphincter muscle and the mucous membrane of the rectum. At the end of the examination, light pressure on the prostate can also provoke the emergence of secretions from the urethra. This secretion can be used for further analysis.

Another examination of the prostate is the determination of the so-called PSA value in blood. The abbreviation PSA stands for P.rostata-sspecific-A.need. This antigen is produced in the prostate. It is actually part of the ejaculate, but a small amount also enters the bloodstream and can thus be determined in the blood. If the PSA level in the blood is increased, the suspicion of a change in the prostate increases. The problem with this examination, however, is that the value can also be influenced by other factors such as older age, benign or harmless changes (like prostatitis) and physical activity and sexual intercourse can be increased.

The PSA value is given in micrograms per liter (µg / l). The guideline value is 4 µg / l. However, the determination of the PSA value is very controversial as a screening method for prostate cancer. However, the value is used in the therapy of prostate cancer as a course parameter.

.jpg)