Juvenile bone cyst

definition

A bone cyst is a fluid-filled cavity in the bone and is incorporated under tumor-like benign bone injuries.

There is also a simple (juvenile) and aneurysmal bone cyst. As the name suggests, the clinical picture of juvenile bone cysts occurs in children and adolescents and is located in the metaphysis.

Read more about the topic here: Aneurysmal bone cyst

This is the area between the diaphysis and the epiphysis and includes the growth plate in children and adolescents. The simple bone cyst is usually located on the humerus (50-70%) or femur (25%). Initially, the bone cysts lie directly on the growth plate, the more you grow, the further away from it (distal) lies this.

In people over 20 years of age, a juvenile bone cyst can also affect the kneecap, shoulder blade or iliac bone. The fluid in the cyst is serous and may be bloody-serous after a bone fracture.

frequency

Only around 20% of bone cysts appear in the second decade of life, most around 65% develop in the first ten years of life. Boys are twice as likely to be affected as girls. Overall, the juvenile bone cyst makes up about three percent of all bone tumors.

clinic

Since the juvenile bone cyst does not cause symptoms immediately, it is mostly discovered by accident. However, it can rarely cause pain and swelling as well as restricted mobility. In 30 to 60% of the cases they are noticeable because of a broken bone.

in the upper arm

The juvenile bone cyst is a benign bone tumor that is most commonly located in the upper arm. The humerus (lat. Humerus) is a long tubular bone in the human skeleton and, along with other long tubular bones such as the thigh, is a typical place of manifestation of the juvenile bone cyst. In the upper arm itself, the juvenile bone cyst usually grows in the area of the Metaphysis. The metaphysis lies between the Epiphysis, the region of the articular head and the Diaphysis, the bone shaft. The juvenile bone cyst is therefore initially located relatively close to the joint area and in the area of the child's growth plate. As the growth process continues, the juvenile bone cyst tends to shift towards the bone shaft.

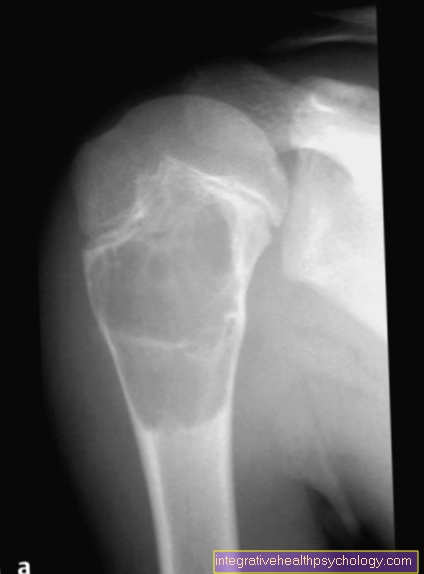

Imaging

Standard imaging here includes x-rays in two planes. It shows a sharply demarcated lesion in the center of the bone. A typical X-ray sign is the “falling fragment sign”. A broken fragment protrudes into the fluid-filled cavity. In addition, a CT or an MRI can be made in order to obtain even more precise information about the juvenile bone cyst.

MRI

In addition to the X-ray, the MRI is another, more precise method in the diagnosis of a juvenile bone cyst. The juvenile bone cyst presents itself in the MRI as a lesion which is filled with fluid and not “chambered”, ie it does not contain several separable spaces. In exceptional cases, however, there may be an untypical septation, i.e. the chamber is separated by a thin septum. The MRI is also used in the diagnosis of a juvenile bone cyst, as it offers the advantage of being able to define the extent of the bone cyst very well and thus to be able to determine the exact size.

In addition, only an MRI can be used to verify the actual presence of fluid. In general, however, the MRI is not always absolutely necessary, as an X-ray image can be meaningful enough to diagnose a juvenile bone cyst. In addition to the fluid-filled cavity, the cyst wall can be described in more detail in the MRI. Characteristically, a delicate cyst capsule without any nodular changes can be seen here. Edema, i.e. an accumulation of fluid around the bone cyst, is only present if there has already been a secondary fracture of the affected bone.

Differential diagnoses

It may be a juvenile bone cyst, but imaging alone is often not enough and other causes of a pathological fracture must be ruled out on the basis of the clinic and any other diagnostic measures. A pathological fracture is a broken bone that occurs spontaneously without any external influence. These other causes include: aneurysmal bone cyst, abscess, giant cell tumor, fibrous dysplasia (a malformation of bone tissue), chondromyxoid fibroma;

treatment

Surgical therapy is not absolutely necessary, as a juvenile bone cyst can regress on its own. Restricting activity is part of conservative therapy. Nevertheless, fractures can occur, which often heal into a bow-leg or knock-kneed leg on the thigh.

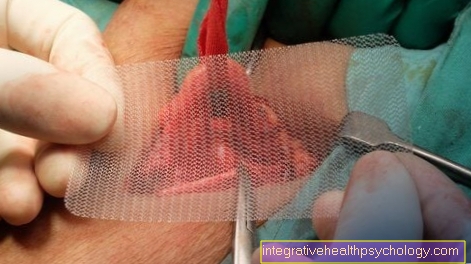

If there is no spontaneous regression, the cyst can be cleared out (a curettage performed) and then filled with cancellous bone (bone material). This is arguably the safest treatment method. However, installing a decompression screw or instilling cortisone can also lead to healing.

In the case of juvenile bone cysts, however, there is no therapy that eliminates the cause. Relapses and fractures can occur with any type of treatment.

When is an operation necessary?

The juvenile bone cyst can partially regress spontaneously and be symptom-free. However, if this is not the case and the juvenile bone cyst causes discomfort in the form of pain and fractures, the indication for surgical treatment must be made. If there is a fracture of the bone in which the bone cyst is located, the surgical treatment of choice is stabilization of the fracture with "elastically stable intramedullary nailing" (abbreviated: ESIN). These are very flexible and, as the name suggests, elastic nails, which are mainly used in children with open growth plates to stabilize a fracture.

The ESIN is mainly used on long tubular bones, as well as the upper arm as the most common place of manifestation of the juvenile bone cyst. In addition, this method is particularly suitable when the growth plate is not yet closed. This is usually the case at the time of surgical treatment of the juvenile bone cyst in childhood. Another possibility is to clear out the bone cyst from a certain size intraoperatively and to refill it with cancellous bone material, which is normally located in the interior of the bone. This is considered a relatively safe procedure that can prevent a fracture.

.jpg)