vein

Synonyms

Blood vessels, veins, body circulation

English: vein

definition

A vein is a blood vessel that contains blood that flows to the heart. In the large body circulation, oxygen-poor blood always flows through the veins, in the lung circulation, however, oxygen-rich blood always flows from the lungs to the heart. Compared to arteries, veins have different structures and functions.

Important veins in the body

The inferior and superior vena cava (vena cava inferior and superior), which carry all of the body's venous blood to the heart. They are the largest veins in the body.

Parallel to this drainage system there is also the azygos or hemiazygos system. These two veins run parallel to the inferior and superior vena cava, lying further on the back and thus offer a second drainage path for venous blood so that constrictions can be bypassed. The veins are almost always named like the associated arteries. Exceptions are, for example, the large rose vein (Great saphenous vein), a superficial vein in the legs, or the internal and external jugular veins (Internal and external jugular veins), which carry the venous blood from the head and neck region back into the superior vena cava.

Special features in the structure

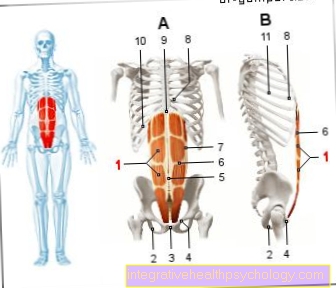

Looking at the microscopic (histological) Structure of the veins, it is found that this corresponds to that of the artery of the muscular type. However, the individual layers of the vein are thinner and looser and contain more connective tissue than arteries of the same size. This can be explained by the fact that the blood pressure in the body's venous system is much lower, so that fewer muscle cells are needed in the vessel wall to counter the high internal pressure.

There are also local differences in veins. In the leg veins, for example, there is a thicker muscle layer in the vascular wall than in the arm veins, as the water pressure in the legs is higher (Hydrostatic pressure) prevails. This is because there is more blood above the legs than above the arms and so the weight of the blood above is higher for the leg veins than for the arm veins.

The outer layer (Tunica adventitia) of the veins is the thickest layer and is often strongly networked with the neighboring tissue. This happens through connective tissue that radiate into the surrounding tissue and thus fasten the vein. Furthermore, the vein is kept open and does not collapse (collapse) when the internal pressure decreases. This ensures that even with low blood pressure and in anemic regions of the body, the blood can always flow back to the heart and is not blocked by closed veins.

Venous return flow

Venous valve

In contrast to the arteries, there is a low pressure in the veins. Thus, the blood from parts of the body that are below the level of the heart cannot be pumped back to the heart so easily against gravity. To facilitate this venous return flow, venous valves are found in all large veins below the level of the heart. Venous valves are folds of the innermost layer (Tunica intima, endothelial layer), which are additionally supported by collagen fiber tissue. The venous valves can prevent the direction of blood flow being reversed, since venous valves only ever allow blood to pass in one direction, namely back to the heart. If blood flows in the opposite direction to that there is no blood flow (standstill), the venous valves inflate like small valve leaflets, lie close to each other and thus close the vein.

Muscle pump

The contraction of muscles allows venous blood to be pumped to the next level of venous valves. This is because many veins are fused with muscles. If the muscle now tenses, contracts and becomes thicker, the shell of the muscle (fascia) that surrounds the muscle and is fused with the veins is stretched. This puts pressure on the blood-filled vein and since the venous valves only allow one direction of blood flow, the blood continues to flow back to the heart.

Other pumping mechanisms of the veins

The venous return flow of the blood is favored by many everyday movements in our body. When running and walking, the pressure of the footstep forces the blood out of the veins in the direction of the heart with every step. Often arteries and veins are also right next to each other. The pressure pulse in the arteries causes compression in the vein, which also pushes blood back to the heart. The heart also plays a crucial role in venous return flow. By shifting the valve level in the heart with each heartbeat, the heart sucks venous blood into the right ventricle with little force (right ventricle, dexter ventricle) on.

Venule

The smallest veins in the human body are called venules. The wall structure of this vein / venule is similar to that of the capillary, but the diameter is significantly larger (10-30 micrometers). A venule has no muscle layer. Often the venule wall is not completely sealed, there are no connections between the individual vessel wall cells (Endothelial cells). This allows white blood cells to get into the surrounding tissue and fight pathogens and inflammation sources there. The passage of white blood cells through the vascular wall of the venules is called diapedesis.

jugular vein

A jugular vein has the ability to close completely. This possibility exists because the jugular veins have an additional longitudinal muscle layer in the innermost layer of the vessel wall (Tunica intima) own. However, this is the exception; normal blood vessels cannot close. This type of vein is found mainly in the intestine and the adrenal medulla.

Portal vein system

The portal vein (Porta vein) collects the venous blood from all unpaired abdominal organs (stomach, intestines, pancreas and spleen) and carries it to the liver. There the blood flows through the capillary system of the liver, where a wide variety of metabolic processes take place. The venous blood then flows through the liver veins (Hepatic veins) into the inferior vena cava (Inferior vena cava).

Vein bulge (sinus venosus)

There are numerous collecting areas for venous blood in the human body. These are called sines (Plural: sine) denotes what bulge means. For example, on Heart the Coronary sinus, a collection point for the venous blood of the heart.

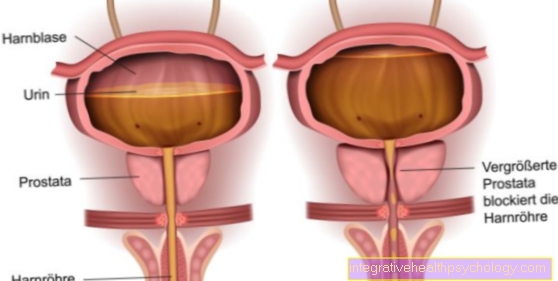

Venous plexus (plexus venosus)

There are also many tiny plexuses and networks of venous vessels in the human body. Small organs and glands are often covered by a plexus of veins (Venous plexus) and thus ensure that the venous blood can flow evenly from all parts of the organ. Likewise, the many windings around an organ, for example in the testicle, create a very large contact area between the organ and the blood vessels, which leads to a more efficient exchange of substances.

Varicose veins (varices)

Varicose veins can have various causes. On the one hand, the venous wall can be very weak in the case of congenital weakness, on the other hand, the venous wall can become weaker as a result of heavy stress (a lot of standing without movement, obstruction of blood flow, for example due to pregnancy).

In both cases, the vein wall gives way, increasing the diameter of the vein.

Due to the larger diameter, the venous valves can no longer close completely and the reversal of the blood flow away from the heart cannot be prevented.

This leads to a backlog of blood, which causes the vein wall to expand further. These so-called varicose veins are then visible. Consequences of the varicose veins can be an undersupply of the tissue from which the vein is supposed to carry the blood away. If the venous blood does not flow out, oxygen-rich blood cannot flow in either, so that the tissue is not properly supplied. As a result, leg ulcers can develop (Leg ulcers).

Furthermore, the disturbed blood flow can cause small inflammation points on the vessel wall. The vessel wall is roughened at these points of inflammation, which means that various blood components are deposited on them and blood clots form. When the blood flow comes back into force, these small blood clots can be carried away and reach the lungs via the heart, where small vessels can then be blocked. A pulmonary embolism occurs, which can also be fatal.

Read more on the topic: Varicose veins

Vein infections (thrombophlebits)

One speaks of phlebitis when superficial veins in the body become inflamed. The causes of such an inflammation are primarily varicose veins on the legs, while the arms can also cause phlebitis from infusions and permanent catheters. The inflammation can cause superficial swelling, but this usually does not affect the flow of blood, as most of the blood is transported back to the heart via veins deep in the body. In the worst case, a bacterial infection can occur and an abscess can also form in the affected vein.

Read more on the topic: Phlebitis