Pyloric stenosis in the baby

definition

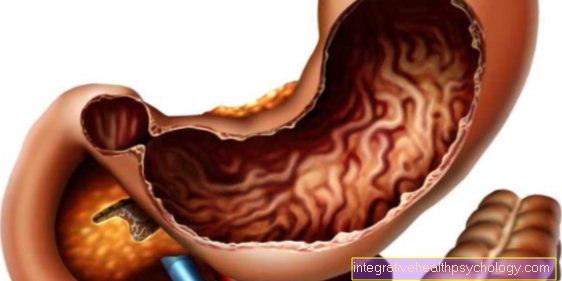

A pyloric stenosis usually becomes noticeable between the second and sixth week of life. Due to a thickening of the muscles of the so-called gastric gatekeeper, the outflow of food is blocked in the area of the gastric outlet. Symptoms include a surge of vomiting immediately after meals, accompanied by a lack of weight gain, a massive loss of fluid and a shift in blood salts. In Germany, between 1 and 3 children per 1000 births develop pyloric stenosis. The risk of illness is increased in premature babies and significantly underweight children and the risk of illness for a boy is four times higher than for girls.

causes

A pyloric stenosis is a thickening of the muscles of the pylorus, the so-called gastric gatekeeper, which regulates the passage of food into the small intestine at the exit of the stomach. For as yet unexplained causes, cramps, so-called spasms, of the pylorus muscles occur again and again. After some time, these lead to an increase in the thickness of the muscle cells, so that only little or, in advanced cases, no more porridge can pass from the stomach to the small intestine. As a result, an emptying disorder of the stomach arises and the stomach contents build up and build up a great deal of pressure until the infant immediately vomits the food it has eaten.

Various factors are considered to be the cause. On the one hand, a genetic predisposition is suspected, since in many cases there is a familial accumulation. On the other hand, changes in the nervous supply and changes in the structure of the smooth muscles are discussed. In addition, a lack of certain nerve endings can be seen as the cause of a lack of relaxation ability of the muscles, which leads to a release of growth factors and thus to a further increase and thickening of the muscle fibers. In addition, infants with blood groups 0 or B are more often affected than infants with a different blood group.

diagnosis

The clinical symptoms provide the first decisive clues for the presence of pyloric stenosis. In order to reliably diagnose pyloric stenosis, however, you need an ultrasound examination and a blood gas test. The blood gas analysis typically shows evidence of a significant loss of fluid, as well as a shift in blood salts in the form of a decrease in potassium (Hypokalemia), a reduction in chloride and an increase in the pH value into the basic range (Alkalosis). If sonographically no clear diagnosis can be made, a missing or delayed passage of food can also be reliably shown or excluded by means of an X-ray contrast agent display of the upper gastrointestinal tract.

Sonography

Sonography is the method of choice for the reliable diagnosis of pyloric stenosis in infants. In most cases, ultrasound shows the stomach to be clearly filled with fluid and with increased activity of the muscles in the right upper abdomen. In addition, a reduced or no transport of stomach contents via the gatekeeper can be shown. As a reliable criterion, an elongated pyloric canal of more than 17 mm and a thickening of the muscles of more than 3 mm can be measured in ultrasound.

Concomitant symptoms

Pyloric stenosis can be accompanied by a variety of accompanying symptoms. However, there are some symptoms that deserve special attention as they make pyloric stenosis very likely.

The characteristic feature is vomiting, which starts about 10-20 minutes after the meal. The infant vomits in a gush-like manner and in a particularly large amount at short intervals. The vomit has a sour odor and in some cases may contain small threads of blood due to irritation of the stomach lining and the lining of the upper digestive tract. There is also a noticeable loss of weight. If one looks at the infant externally, the gatekeeper can sometimes be seen or felt as an olive-sized, rounded structure in the right upper abdomen. In addition, the increased movement of the stomach muscles is often visible as a wave-like movement of the abdominal skin. Due to the resulting loss of fluid, the skin of the affected infants appears dry and typical signs of dehydration appear, such as a sunken fontanel, deep circles under the eyes or standing skin folds. In addition, due to the lack of fluids, the infants pass significantly less urine and are often very restless and drink particularly greedily. As a result of vomiting, the infants lose not only the liquid but also the acidic gastric juice, which leads to a shift in the pH value into the basic range (Alkalosis) is coming.

Therapy / OP

If there is a pyloric stenosis, there is a prescribed treatment guide that one should adhere to.

First, oral feeding is stopped immediately. The existing loss of fluids and electrolytes is compensated for by the supply of infusions. In addition, if the vomiting persists, a tube can be inserted into the stomach through the nose to relieve the strain.

The following standard therapy is the operative splitting of the thickened pylorus muscles, the so-called Pylorotomy. This is performed under general anesthesia and can be performed both through an open surgical procedure and with the help of minimally invasive surgical procedures, such as endoscopic (laparoscopy) can be made.The aim of surgical treatment is to split the muscles of the gastric porter lengthways without damaging the mucous membrane. The muscle ring at the stomach outlet is pulled apart, thereby increasing the diameter in order to ensure unhindered transport of food. In order to detect an accidental opening of the mucous membrane at the junction between the stomach and the small intestine, you can put air into the stomach via a gastric tube during the operation and see whether a defect is noticeable with the escape of air. An early operation is particularly recommended, as the infants are still in good general condition at an early stage and the chance of complications is reduced as a result.

Read about this too Anesthesia in children - procedure, risks, side effects

forecast

The mortality is very low at around 0.4% and in most cases is not due to complications of the operation, but rather to a previously inadequate and inadequate compensation for fluid losses and shifts in blood salts. The prognosis after surgical splitting of the pyloric muscles is very good. Only in rare cases do complications arise, such as wound infections, incomplete splitting of the muscles, or accidental opening of the mucous membrane at the transition from the stomach to the small intestine.

.jpg)